Fine-Art „Giclée“-Print on canvas – stretched over a wooden frame with a depth of 2 cm

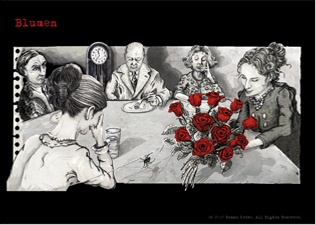

Illustration by Roman Kroke (2009)

Mesures: 40 cm x 30 cm

Customized title: language freely selectable – please specify the language of your choice during the order (in the preview: French)

Annotations to the illustration by Roman Kroke:

I created the illustration on the basis of the following citations from Etty’s diary:

“Many say, “How can you still think of flowers!” Last night, walking that long way home through the rain with blisters on my feet, I still made a short detour to seek out a flower stall, and went home with a large bunch of roses. They are just as real as all the misery I witness each day.”

23 July 1943

“What is at stake is our impending destruction and annihilation, we can have no more illusions about that.”

3 July 1942

For Etty, the flowers bring some colour (= joy) into her life. I carried this idea over to the illustration. The RED brings colour into the black and white picture.

The clock metaphor: due to its location in the picture, the clock seems almost to be sitting facing the table like another person. I imagined the atmosphere in the room: the other people’s incomprehension regarding Etty’s love for flowers despite the hostile circumstances at that time – oppressive silence at the table – time elapsing, interrupted only by the ticking of the clock. In this silence, the clock with its mechanical sounds has a brutal presence, just like another human being sitting at the table. The clock reads twenty-four minutes to twelve. The German saying “It is five minutes to twelve” expresses that something menacing is going to happen soon – at 12 o’clock. At the time depicted in the illustration (23 July 1942), the situation of Etty and her family has not reached this fatal point – not yet. This is why the clock still reads twenty-four minutes to twelve. But time will move on. About one year later, on 7 September 1943, Etty and her family will be deported to the extermination camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau. According to a Red Cross report, Etty dies three months later (30 November 1943).

With the second excerpt, I want to point out that, despite her unbroken passion for flowers, Etty was in no way a dreamer who tried to flee from reality into a make-believe world. The excerpt, chronologically located before the previous one, shows that she was entirely aware of the brutality of their imminent fate. Etty’s efforts to preserve her sensibility for small pleasures seems to me to have been something from which she could draw strength and maintain her love for life.